When C.S. Lewis and his brother Warnie were young, they enjoyed writing about two different worlds—Jack’s was filled with brave adventures and talking animals (it was called “Animal-Land”), and Warnie’s was essentially modern-day India, with a lot of emphasis on trains and politics and battles. They folded these two together and created an imaginary world called “Boxen.”

The medieval adventures of Animal-Land gave way to frogs in suits and King Bunny having goofy semi-political adventures that involved a great deal of standing around and some societal farce. The stories aren’t terrible at all, especially given that they were made by kids. Lewis called much of his early work “prosaic” with “no poetry, even no romance, in it.”

One of the main problems with Boxen, according to Lewis, was that he was trying to write a “grown-up story,” and his impression of grown-ups was they talked endlessly about rather dull things and had meaningless parties and so on. So that’s what his stories were about, too.

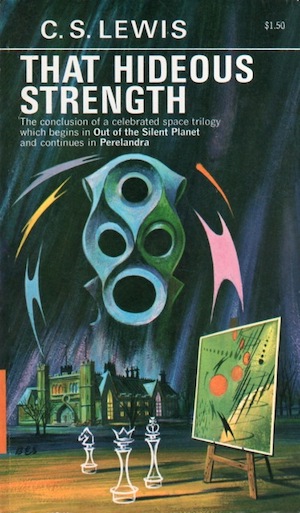

That Hideous Strength is the third novel in Lewis’s Space Trilogy. It’s also the longest of the three books, and the only one to take place entirely on Earth. The subtitle is “A Modern Fairy-Tale for Grown-Ups.” (This is almost certainly an echo of George MacDonald’s Phantastes, which was subtitled “A Faerie Romance for Men and Women.”) The title itself is a reference to a poem by David Lyndsay, which, referring to the Tower of Babel, says, “The shadow of that hyddeous strength, sax myle and more it is of length.”

The Tower of Babel, of course, being the story of humanity thinking that they can, by their own power and skill, build a tower to Heaven. God sees this and intervenes by confusing the languages of humanity, breaking up human society into different groups.

I have been dreading re-reading this book. When I read it as a kid, I disliked it. I couldn’t remember anything I liked about it. I’m sure I didn’t understand it, for one thing, but nothing from the book (other than a vivid memory of The Head) stuck with me.

So it was with some trepidation that I picked it up and started reading it. I know, too, that a number of you who have been on this reread journey love the book! As I read I felt growing dismay as I went from mild annoyance to boredom to pure burning hatred. I was maybe a third of the way through the book and I was ready to throw it out a window.

I understood it better than when I was a kid, but everything about it was making me angry. Our main character, Ransom, is nowhere to be seen. There is no journey to outer space, no adventure, no “romance” in the Lewisian definition. Even Lewis the narrator has mostly disappeared. I started to wonder if Lewis was, for lack of a better way of saying it, trying to “write something for the adults.”

Lewis seemed to be aware that this was a possible response to the book. In his preface he says:

I have called this a fairy-tale in the hope that no one who dislikes fantasy may be misled by the first two chapters into reading further, and then complain of his disappointment. If you ask why—intending to write about magicians, devils, pantomime animals, and planetary angels—I nevertheless begin with such humdrum scenes and persons, I reply that I am following the traditional fairy-tale. We do not always notice its method, because the cottages, castles, woodcutters, and petty kings with which a fairy-tale opens have become for us as remote as the witches and ogres to which it proceeds. But they were not remote at all to the men who made and first enjoyed the stories.

Of course I was having the opposite experience, badly wanting more fairies and fewer humdrum scenes. I texted a friend and told him that so far, the main characters had argued about whether the University should sell a certain plot of land, had considered a job change, and one of them had gone out to buy a hat.

I’ll say that Ransom’s arrival brought much more of what I wanted into the book: the adventure, the supernatural, some really wonderful moments (like the arrival of Merlin!) and some thrilling scenes of mortal and spiritual danger. By the end I was frustrated, but still glad I had read the book. And we’ll have plenty of time to talk about some of those things! In the meantime, some things to look for as you read along, if you want to join us as we continue to discuss the novel:

- Lewis tells us straight out that this is the fictional version of his (quite short!) book The Abolition of Man. In fact, the ideas there play a major role in the redemption of our main characters. If you feel at all confused about Lewis’s point(s) in That Hideous Strength, take a couple hours and read The Abolition of Man.

- Lewis never was a man to keep his opinions to himself, so be prepared to hear a (at that time) confirmed bachelor critique other people’s marriages and even make crochety comments about the younger generation’s ideas about it. Honestly, I feel like one of the major things I hate about this book is how much Lewis wants to say about things he understands very well (like higher education in Britain) and that he wants to say just as much about things he doesn’t understand well at all (like what it’s like to be married).

- You’ll notice there are some characters who appear to be caricatures of real people, and you’re correct! “Jules” for instance, has a great deal in common with H.G. Wells (who we already know Lewis was critiquing with the Space trilogy).

- If you have read any Charles Williams, it really will help you understand what Lewis is trying to do in this book. Williams wrote metaphysical thrillers, and Lewis is absolutely trying to write a Williams novel here. I really enjoy the gonzo weirdness and unexpected thrills of a Williams novel…and I don’t think Lewis quite captured it.

- Note the emphasis on liminal things…things that are not quite this or that. Merlin is the most obvious, but you will see a lot of references throughout to borders, edges, things that appear to be one thing but maybe are something else. (Even politics…both our heroes and the evil bad guys agree that political sides are unimportant. It’s not about Left or Right—there’s a liminal space of greater importance.)

- This is a great time to review your Arthurian legends. Look especially at the story of the Fisher King (and the “dolorous blow”), stories of Merlin and his origins, and anywhere the knights interact with those who have fairy roots.

- This is no real surprise, but names are chosen with care in this book. Anyone who appears from a previous book gets a new name in this one (one shocking instance is mentioned in a throwaway comment and never pointed out again). Names like “Hardcastle” and “Ironwood” have purposeful roles in the text.

- Visions and dreams are, of course, of great importance, so pay attention to those!

- There is a core argument about beauty, Nature, and what those things should work in human beings, as well as how the enemies of The Good will interact with those things. Watch for Nature and our relationship to it… especially as it relates to Ransom and the company of St. Anne’s, Merlin, and the people of N.I.C.E. There are three very distinct approaches, and Ransom in particular has strong opinions on the topic.

- Punishment—what it is, its relationship to justice, and what is healthy and good when it comes to the penal system—is another core question of this book. Or rather, core point: there’s no real question. The bad guys think one thing, the good guys find it disgusting.

- A minister named Straik gets several detailed speeches. These are worth looking at carefully. Lewis is talking about how religious people find themselves working for the wrong side, and Straik is an interesting example (if lacking in nuance… but hey, welcome to That Hideous Strength).

- There’s lots of talk of marriage and gender (Lewis mentions again that there are seven genders in the cosmos, and I really wish he had spent more time on this). It’s worth thinking about how men and women differ if they’re on the side of N.I.C.E. or if they’re working with Ransom.

- Be sure to note what Ransom eats and drinks nowadays!

- There’s a fun proto-Narnian feel to the way Nature interacts with our heroes, especially with good old Mr. Bultitude, and note Ransom’s mice friends…another indication of the author’s long-standing affection for the little rodents who lived in his homes.

- Anytime someone says “what the devil” or something along those lines, expect that Lewis means this quite literally. It’s said often in this book.

- Watch for discussions of obedience and permission, and pay close attention to what N.I.C.E. actually hopes to accomplish in the universe, and how they explain it to themselves as well as to Mark.

- Related: the bad guys are definitely eugenics-friendly. But weirdly, the good guys also place a strong emphasis on bloodlines to accomplish something good. I’m not sure if this was intentional, but worth reflecting on.

- Religious conversion is a theme. The stomping of the crucifix is a scene to note.

- Be sure to note who lives in Perelandra now!

- There are many Biblical references, but given the theme of punishment, watch for how the echoes of Babel, Sodom and Gomorrah, and Hell enter the story.

- Fun little asides to notice: Tolkien’s Númenor is mentioned maybe three times. Note what Ransom calls the top floor of the Manor. Two of Ransom’s company (Ivy and Margaret) have the same names as women who were the servants of a certain Professor Kirke in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The heavenly archetypes certainly push the balance toward the Planet Narnia readings of the Chronicles, it seems to me.

- And finally, a bit of trivia! George Orwell wrote a review where he complained a good bit about That Hideous Strength. His opinion was the opposite of mine: he loved the intrigue and the “crime” and was thrilled by the idea of a horrific leader who was overseeing everything. He wished Lewis would have left out all the fairies and Merlin and angels out of it. You know…kind of like his own novel, 1984, which would come out a few years later. Anyway, it’s a fun little critique and you can read it here.

I laughed out loud at Orwell’s last sentence: “However, by the standard of the novels appearing nowadays this is a book worth reading.” This is surely my least favorite of Lewis’s novels—but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth a read. See you in two weeks and we’ll dig a little deeper!

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.

Matt Mikalatos is the author of the YA fantasy The Crescent Stone. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.